The Korea-ASEAN Solidarity Initiative: Recalibrating Socio-Economic Connectivity

Published

Melinda Martinus scrutinises softer prospects of the new ASEAN-Korea relationship.

The Republic of Korea (ROK) announced the Korea-ASEAN Solidarity Initiative (KASI) at the ASEAN-ROK Summit in Phnom Penh last year. The initiative represents Korea’s growing efforts to strengthen its Indo-Pacific Strategy and broaden its international engagement beyond its traditional four major partners: China, the United States, Japan and Russia.

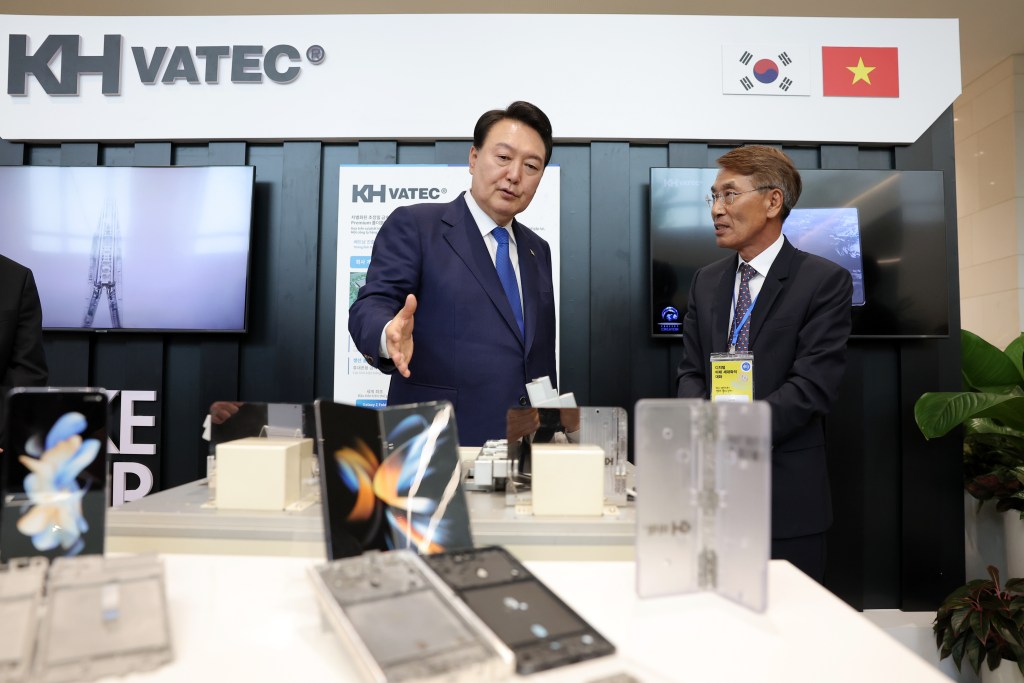

A key motivation behind KASI is to deepen strategic and security alignment in ASEAN. Many analysts criticised the New Southern Policy (NSP) led by the previous administration under President Moon Jae-In for its lack of security elements and only limited to functional economic and development cooperation. Under KASI, the new administration led by President Yoon Suk Yeol aims to pivot to security-driven initiatives, including defence exchanges and joint responses to regional challenges such as cyber and maritime security.

While security cooperation leaves much to be desired in ASEAN-ROK relations, especially now that the Yoon Administration has displayed a strong preference for strengthening its alliance with the US in the Indo-Pacific, KASI should not ignore functional socio-economic cooperation. In fact, gaps and opportunities remain in functional cooperation, such as deepening trade and improving trust through soft diplomacy, despite the relationships between the two sides having achieved significant milestones in the past few years. There are four areas to look at.

First, mutual trust between both sides could have been better. According to The State of Southeast Asia 2023 Survey conducted by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, ASEAN opinion leaders rank South Korea relatively low in economic, strategic, and soft power influence compared to other major powers. Only 1% of ASEAN elites think that the ROK is an influential economic power, putting the ROK in 8th position out of a ranking of nine countries. Similarly, a survey conducted by the ASEAN-Korea Centre on Mutual Perceptions of ASEAN and Korean Youths indicated that interest in ASEAN among Korean youth is relatively low, with only 52.8% of Korean youth stating interest in ASEAN. On the other hand, the excitement of ASEAN youths towards Korea is exceptionally high, with 97.7% of them showing interest. These external and internal perceptions challenge Korean policymakers in articulating their foreign policy strategy towards ASEAN.

Second, despite praises for the Moon administration’s efforts in deepening economic connectivity with ASEAN – from increasing the number of Korean investments and consumer goods entering the ASEAN market – connectivity is somewhat still asymmetrical. South Korea relies predominantly on a single ASEAN member, Vietnam, for its exports. Currently, 48% of the total Korean export volumes to ASEAN goes to Vietnam. Similarly, 27% of Korean Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to ASEAN goes to Vietnam, making Vietnam the second main destination for Korean FDI after Singapore.

Where soft power is concerned, South Korea has not optimally tapped into the rising tourism appetites of Southeast Asia’s middle-class. Despite ASEAN accounting for a larger population, the number of ASEAN citizens visiting Korea is only one-fifth of the number of Korean tourists to ASEAN in 2019 (prior to COVID-19). In fact, despite the popularity of Korean pop culture in the region, South Korea is still a less attractive destination for ASEAN visitors. Japan topped ISEAS’ latest survey as the most favoured tourism destination for ASEAN citizens, registering 27.3% of total respondents versus South Korea’s 7.2%.

The ROK’s depth and maturity of economic connectivity with ASEAN member states vary considerably. At the regional level, South Korea has requested for an ASEAN-ROK Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Status (CSP) and has successfully acceded to an ASEAN-led trade initiative, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in 2022. At the bilateral level, the ROK has free trade agreements with Cambodia, Indonesia, Singapore, and Vietnam. The Korea-Singapore Digital Partnership Agreement (KSDPA), which set a precedent in regional digital economy cooperation, was adopted in January 2023. These ambitions signal that there are still untapped opportunities beyond traditional trade cooperation.

Third, the geopolitical environment has changed since President Moon launched the NSP in 2017. Then, the main motive for the ROK to pivot towards ASEAN was the need for greater market diversification. China’s boycott of Korean goods due to the ROK’s decision to permit the US deployment of a THAAD missile defence system exposed Seoul’s overreliance on the Chinese market for its exports. Thus, it was necessary for Seoul to diversify its trade activities and find a more stable export destination, making ASEAN a suitable alternative due to its economic growth prospects.

With the trade war between China and the US intensifying and fragmenting the global trade regime, South Korea needs to recalibrate its global supply chain strategy. Tariffs and trade tensions forced Korean multinational companies to rethink their supply chain strategies, leading to diversification away from China. Beyond being an attractive market for Korea’s exports, ASEAN is also a critical partner in their global supply chain. Enabling policies can help ASEAN and the ROK play a complementary role in the global value chain (GVC), with South Korea supplying advanced components and technology while ASEAN countries provide manufacturing, assembly, logistics, and delivery across the region and globally. This would strengthen economic resilience amid an uncertain geopolitical situation.

Lastly, the ROK aspires to be a global pivotal state. While it is true that the ROK needs to showcase a ‘hard security’ component in its international diplomacy, including strengthening defence cooperation with ASEAN, the truth is that gaining a global reputation is beyond just increasing military capacity. The Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index 2023, which measures regional power influence using various criteria such as economic capability, and diplomatic and cultural influence, placed South Korea in the 7th position, below Australia and just above Singapore and Indonesia.

Among 29 Organization for Economic Cooperation Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) countries, South Korea ranks 16th in terms of total official development assistance (ODA), disbursing US$2.2 billion in ODA to developing countries in 2020. As a benchmark, Japan distributed US$16.6 billion ODA globally. It is thus not surprising that Japan continues to gain trust and is perceived as a credible partner to hedge against the uncertainties of US-China rivalry, according to the ISEAS Survey. South Korea’s commitment to double its ODA by 2030 is a welcome development for ASEAN, especially for less-developed member countries that need assistance to achieve their sustainable development goals.

South Korea has successfully built an image as a reliable regional partner in the economic and people-to-people aspects. The efforts built by the Moon administration and the forward-looking agenda under President Yoon should pave the way for more tangible cooperation moving forward. This would strengthen partnerships in GVC reconfiguration and emerging sectors such as the digital economy and sustainability.

The anniversary of the ASEAN-ROK commemorative summit next year can provide some momentum to showcase KASI’s tangible objectives, including renewed socio-economic commitments. The ASEAN CSP will be granted but the ROK must demonstrate commitment in deepening partnership with ASEAN in all aspects.

Editor’s Note:

This article is part of ASEANFocus Issue 2/2023 published in September 2023. Download the full issue here.

Melinda Martinus is the Lead Researcher in Socio-cultural Affairs at the ASEAN Studies Centre, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.