Indonesia Shepherding an ASEAN Digital Community

Published

A truly regional digital community with borderless transactions and equitable access to online services must start with actual progress in the smallest of goals for an ASEAN-wide digitisation and digitalisation.

Indonesia has consistently been ambitious as ASEAN Chair. Under Indonesia’s Chairmanship, ASEAN introduced the ASEAN Community in 2003 and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in 2011. It is not a surprise that as this year’s ASEAN Chair, Indonesia is aiming high. One of the key goals that Indonesia aspires to is to bring ASEAN closer to a single regional digital community by launching the ASEAN Digital Economy Framework Agreement (ASEAN DEFA).

ASEAN has made important strides in building this digital community. Most recently, on 9-10 February 2023, the ASEAN Digital Ministers adopted the Boracay Digital Declaration, “Synergy Towards a Sustainable Digital Future”. Guided by the ASEAN Digital Masterplan 2025 and the Bandar Seri Begawan Roadmap, the Declaration recognises the importance of a digitally inclusive society by addressing the digital divide; a trusted, secure and safe digital market by adopting necessary digital data governance including data management, cybersecurity, and AI governance; and people-centred digitalised government.

Under Indonesia’s chairmanship, ASEAN will complete its feasibility study for the ASEAN DEFA and start negotiations to be concluded in 2025. DEFA is inspired by so-called “digital-only” agreements (digital economy agreements or DEA). Unlike digital provisions in conventional trade agreements that typically focus on market access, DEAs aim to facilitate cross-border collaboration on wide-ranging issues such as cross-border data flows, personal data protection, AI governance, and digital ID systems. At present, Singapore is the only ASEAN member state (AMS) that has signed DEAs: it has Digital Economy Partnership Agreements (DEPA) with Chile and New Zealand, the Singapore-Australia DEA, the United Kingdom-Singapore DEA, and the Korea-Singapore Digital Partnership Agreement.

A major barrier against achieving an ASEAN-wide digital future and a high-standard DEFA is the vast disparity among the different AMS in terms of their readiness for true region-wide digital integration. A measurement for country-level digital readiness is the ASEAN Digital Integration Index, which looks at six dimensions of digital integration readiness, namely: digital trade and logistics, data protection and cybersecurity, digital payments and identities, digital skills and talent, innovation and entrepreneurship, and institutions and infrastructure. Malaysia and Singapore scored above the regional average, while Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Myanmar scored below in all six dimensions in 2021. Meanwhile, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, the Phillippines and Brunei Darussalam had mixed scores.

As the Index suggests, the regulatory framework for data safeguards remains unevenly regulated in ASEAN. For example, on passing personal data protection laws, Singapore, Malaysia, and the Philippines were the early movers, while Thailand and Indonesia passed such laws only in 2022. Vietnam aims to pass its data privacy law by 2024. Besides data safeguards, there are regulatory disparities with regard to de minimis provisions (i.e., the minimum value of goods below which no tariffs or taxes are collected at borders), taxation, subsidies, and industrial policy, competition or antitrust policies, as well as data localisation.

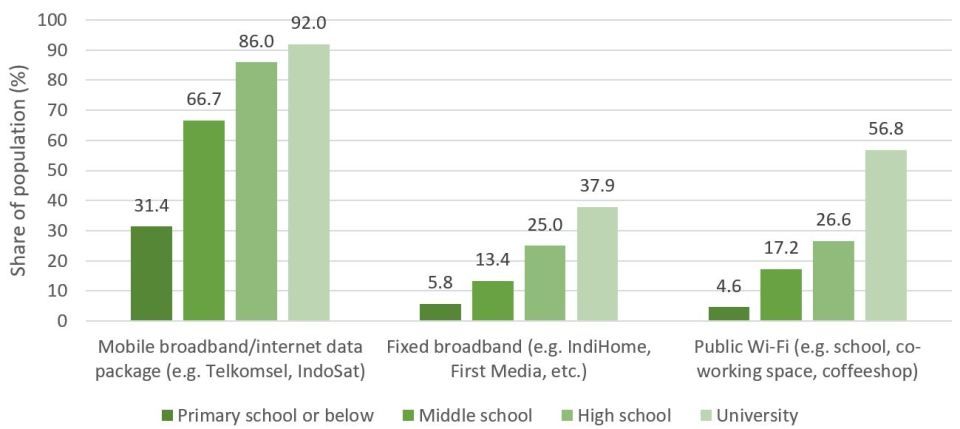

This disparity also exists within countries with lower-level development, including Indonesia. An opinion poll by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and Lembaga Survei Indonesia (LSI) in July 2022 reinforced the findings on Indonesia’s digital divide. The survey shows that this divide is especially glaring across populations with different education levels. For example, for those with primary education or less, less than a third and less than 10 per cent access the internet via mobile broadband and fixed broadband, respectively. In sharp contrast, 92 per cent and more than one-third of those with university and equivalent education use mobile and fixed broadband for internet access, respectively (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Channels for Individuals’ Access to the Internet, Indonesia, 2022

To achieve a sustainable digital future, ASEAN could focus on the following three key areas and action plans (see Figure 2 below):

First, to develop a trusted and integrated digital market. ASEAN could prioritise setting standards on data safeguards and harmonising regulations to ensure a fair distribution of benefits across all AMS and all types of enterprises in a more integrated regional digital economy. ASEAN could give capacity building or technical assistance to AMS which lag behind. Under Indonesia’s Chairmanship, for a start, ASEAN plans to deliver three concrete outcomes, namely, an ASEAN QR code as a common digital payment and currency, a digital lending platform for matching potential investors and lenders, and Wiki Entrepreneurs as a one-stop digital platform for ASEAN micro and small enterprises.

Second, to build a digitally inclusive society. ASEAN could prioritise accelerating universal access to digital connectivity (especially for 4G networks and fixed broadband) and preparing current and future workers for fast-changing digital transformations, while ensuring that current labour laws, definitions, and standards are well suited for the changing nature of jobs. ASEAN could also design consumer rights and protection standards that are interoperable across ASEAN. Given concerns about the impacts of digital transformation on mental well-being, ASEAN could perhaps even aspire towards having a mental well-being Charter.

Third, to forge a digitalised government service system. ASEAN could prioritise creating a digital ID system for all AMS, working towards regional interoperability for national ID systems. ASEAN could aspire to have mutually recognised electronic identification like the EU’s eIDAS (Electronic Identification, Authentication and Trust Services) system and work towards the implementation of the Once-Only Principle (OOP). With such an integrated ID system in place, an ASEAN citizen would need to provide certain standard identification information to regional authorities and administrations “once and only” once. Further, ASEAN could set up a standardised digitalised Public Service Delivery (PSD) platform. Last, citizens’ e-participation could serve as a feedback mechanism.

To realise its plans, Indonesia’s ASEAN Chairmanship could focus on concrete deliverables in the short run, such as the ASEAN QR code, while laying out the foundations for future ASEAN chairs to push ahead with a trusted and integrated regional digital market, more inclusive digitally connected societies, and digitalised government systems in the long run.

Figure 2. Three key focus areas and action plans for an ASEAN digital future

Indonesia’s ambitious plan to launch the ASEAN DEFA and to move closer to an ASEAN digital future is commendable, given that the digital future is right at our doorstep. Ideas have also been brewing about an ASEAN Digital Community by 2040. To realise its plans, Indonesia’s ASEAN Chairmanship could focus on concrete deliverables in the short run, such as the ASEAN QR code, while laying out the foundations for future ASEAN chairs to push ahead with a trusted and integrated regional digital market, more inclusive digitally connected societies, and digitalised government systems in the long run. ASEAN may have no choice but to set short-term targets to achieve more difficult long-term targets, such as regional interoperability for national ID systems. Domestic obstacles, especially Myanmar’s intractable civil war and broader geopolitical realities, especially the U.S.-China technological bifurcation, will pose serious risks to digital integration in ASEAN.

2023/61

Maria Monica Wihardja is a Visiting Fellow at ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the National University of Singapore.

Ibrahim Kholilul Rohman is a Senior Research Associate at the Indonesia Financial Group Progress (IFG Progress). He is also a lecturer on Digital Economics at Faculty of Economics and Business and School of Strategic and Global Studies, Universitas Indonesia.