Ismail Sabri as the New PM: An Uneasy Truce

Published

The appointment of Ismail Sabri Yaakob as Malaysia’s ninth prime minister is welcome. At best, however, his ascent represents an agglomeration of compromises between the players concerned. As the country experiences another Covid-19 surge, he will have his work cut out for him.

After months of political uncertainty and tension, it has become increasingly apparent that Ismail Sabri Yaakob may succeed Muhyiddin Yassin, who resigned as prime minister on Monday. This change alone should bring a sigh of relief to Malaysians, who have had to witness the political ructions in Kuala Lumpur as they grappled with the surging Covid-19 pandemic and the resultant economic pain.

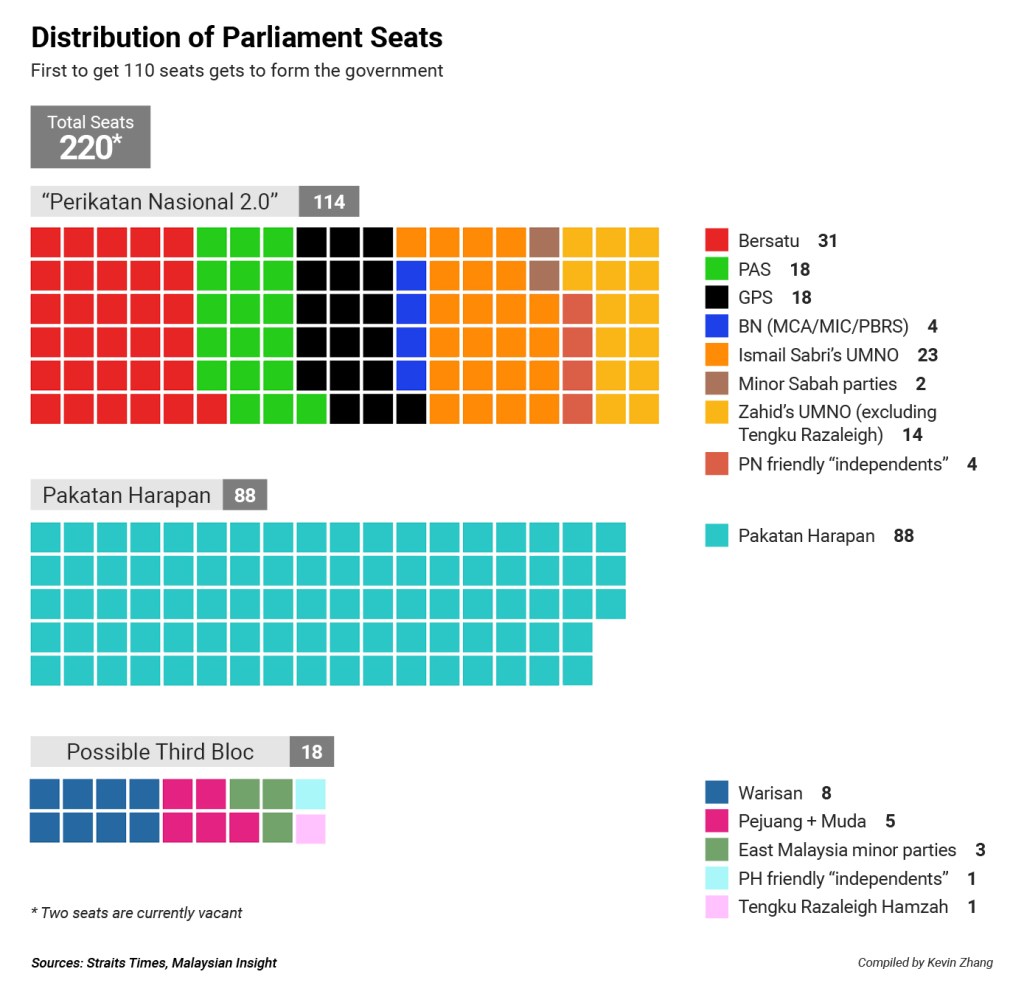

That said, the appointment of Ismail Sabri, a vice president of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and former deputy prime minister serving under Muhyiddin, does not mean that much has changed. The country is back with the same group of Members of Parliament (MPs) in power. The only difference between this government and the last is that it has one less MP, and it is reorganised under a new leader. 114 MPs backed Ismail Sabri to become the ninth prime minister, three more than the required threshold. This means Barisan Nasional, a coalition that UMNO leads, is back in the driver’s seat after losing power in 2018. This is significant; that said, it was with UMNO’s backing of 38 MPs that propped up the previous Perikatan Nasional administration under Muhyiddin.

If Ismail Sabri is appointed as prime minister, the country shall avert from another leadership crisis. Yet, the prime minister’s slim majority, similar to what Muhyiddin had when he became prime minister in March 2020, means that political uncertainty will remain. The King has urged the new prime minister to test his support through a vote of confidence, but with this small majority, any defection will spell trouble for UMNO. Moreover, what tips the balance in Ismail Sabri’s favour is four independent MPs. Until an anti-hopping law is passed, no sitting government can be sure of MPs’ loyalty. Fortunately for Ismail Sabri, the King has warned MPs to focus on the tasks at hand, especially the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic. The King is also calling for unity, warning politicians to avoid considering the government and opposition as “winners” and “losers”. This uneasy truce may last until the next election, likely to happen next year.

Despite having a new prime minister, the ruling and opposition coalitions continue to be fragmented. To be sure, the Barisan Nasional under Ismail Sabri is not the same coalition Mahathir Mohamad helmed between 1981 and 2003. In those halcyon days, BN coalitions were able to secure two-third majorities in Parliament. Currently, even the Sarawak-based parties are not formally part of the coalition, and no one can stop them from considering carrots from the opposition.

The bigger question is how the rank and file in Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia will perceive UMNO’s move to displace Muhyiddin, Bersatu’s chairman. Heading into the next general election, there is no guarantee that UMNO will allow Bersatu to contest in the seats it won in 2018. After all, UMNO competed for those seats too. UMNO must be careful not to make Bersatu feel like a junior partner, since UMNO had previously displaced the latter’s chief ministers in Johor and Perak. It is only in Sabah that UMNO compromised and allowed Bersatu’s Hajiji Noor to become chief minister despite Bersatu holding fewer seats than UMNO.

The bigger question is how the rank and file in Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia will perceive UMNO’s move to displace Muhyiddin, Bersatu’s chairman.

In retrospect, many in Bersatu will be left scratching their heads recapping the chain of events that led to Muhyiddin’s ouster. There are many imponderables. 15 UMNO MPs quit Perikatan Nasional, causing Muhyiddin to lose his majority. But they then agreed to support Ismail, who was Muhyiddin’s deputy. Was Ismail Sabri party to the UMNO withdrawal? Was UMNO only upset with Muhyiddin but not Ismail Sabri? Should not the previous Cabinet be collectively responsible, and Ismail Sabri too be blamed for the Muhyiddin government’s shortcomings? Moreover, Muhyiddin’s last address as prime minister was that he would not be arm-twisted into influencing court decisions involving some UMNO leaders. In response, Najib Razak has sued Muhyiddin for defamation. One does wonder how strange bedfellows such as Muhyiddin and Najib can end up in the same political coalition. Questions also remain regarding the future of 11 former Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) MPs among the current 31 Bersatu MPs. They include Azmin Ali and Zuraida Kamaruddin, who left PKR under a storm of controversy. With Ismail Sabri’s slender majority, this group can also determine whether he stays or goes.

On the other hand, the opposition has its problems too. In September last year, opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim claimed to have assembled a strong, formidable, and convincing majority to become prime minister. This was not tested because no vote of confidence motion was tabled. Yet, he again failed to prove his support during this unique window of opportunity after Muhyiddin’s resignation. Earlier, there was bargaining between Anwar and Shafie Apdal. But the latter, who is president of Parti Warisan Sabah, then backed out and lent his support to Anwar. Mahathir’s camp of four MPs too supported Anwar, quashing rumours that he was against Anwar becoming the prime minister. Sarawak-based party GPS later admitted that Anwar never reached out to them for support. Clearly, with his failure to garner support, the opposition may need to look beyond Anwar and start looking at a potential successor.

As it is, Ismail Sabri must be given the room to lead Malaysia out of this crisis. He is seen as a clean leader with no court cases. However, this image will depend on how he deals with the ongoing legal cases involving UMNO leaders. In an open letter, this was also Muhyiddin’s appeal for him to exclude MPs with court cases from the Cabinet. Ismail Sabri must quickly reverse the negative association with the previous Muhyiddin government, which was deemed inefficient in dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic. The country now hopes Ismail Sabri can be the unifying figure in the country. But gaining support from other Malay parties such as Bersatu and Dr Mahathir’s Pejuang may not be as arduous as finding practical solutions to the country’s health and economic problems.

2021/212

Norshahril Saat is a Senior Fellow and Coordinator at the Regional Social & Cultural Studies Programme, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.